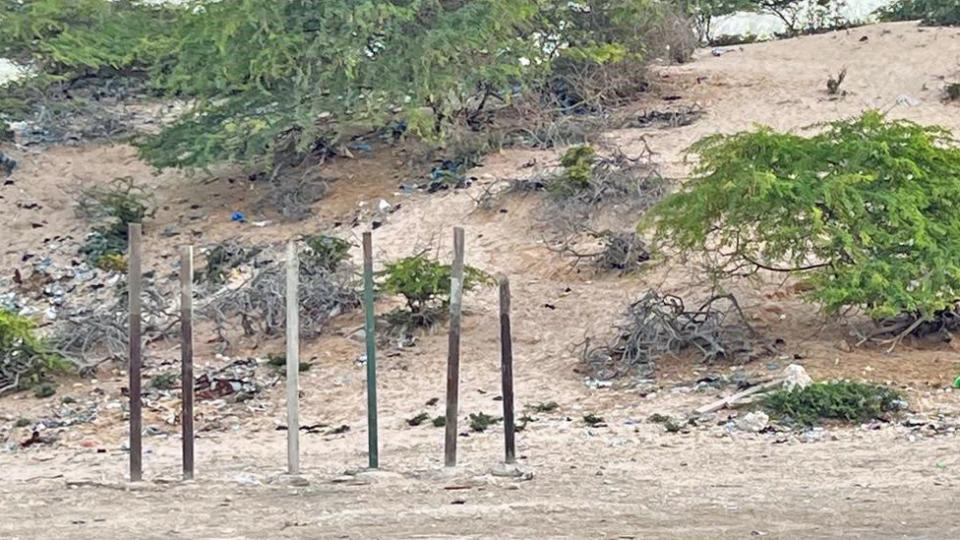

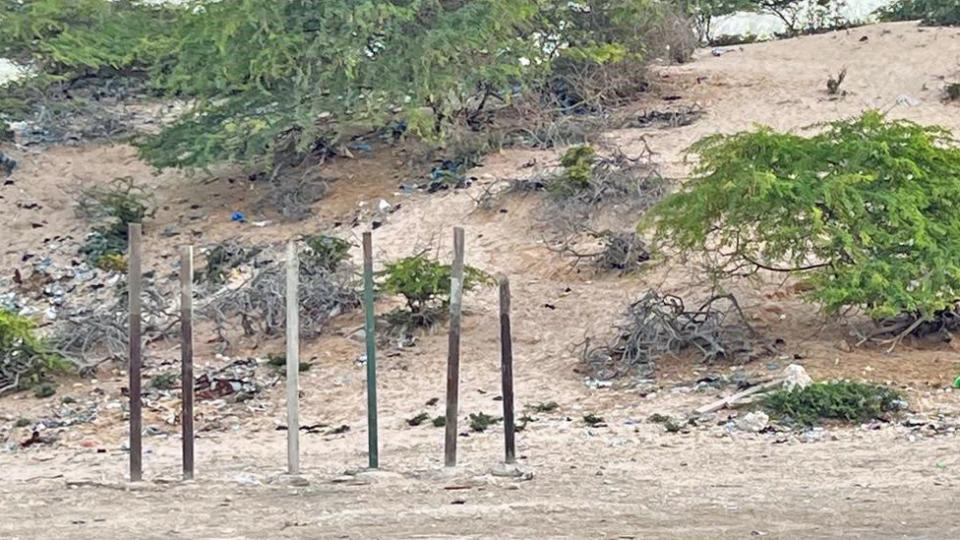

On the beach in Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia, six tall concrete pillars stand on the pure white sand. The bright blue waves of the Indian Ocean crash quietly nearby, often bearing witness to harrowing events.

Warning: This article contains language that may be upsetting to some people

Security forces sometimes bring men here, tie them to pillars with plastic rope, put black hoods over their heads, and shoot them.

Specially trained members of the firing squad also cover their faces.

The dead man's head hangs down, but his body remains upright, tied to a post. Their tattered shirts and sarongs flutter in the wind.

Some have been convicted by military courts of belonging to the Islamist group al-Shabab, which has been spreading terrorism in Somalia for nearly two decades and controls large parts of the country.

Some soldiers have been convicted of killing civilians or colleagues. Sometimes courts deal with common criminals whose crimes are so serious that they have been sentenced to death.

At least 25 people were executed on the beach last year.

The most recent person facing the death penalty is Syed Ali Moalim Daoud, who was sentenced to death on March 6 for locking his wife, Lulu Abdiaziz, in a room and setting her on fire. He allegedly burned her alive because she asked for a divorce.

Immediately behind the killing scene is the small informal settlement of Hamar Jadjab, home to about 50 families in a former police academy full of crumbling homes and makeshift shelters.

“As soon as my five young sons come home from school, they run to the beach to run around and play soccer,” says Fatun, one of the coastal residents of the former police training center. Mohammed Ismail says:

“They're using execution poles as goalposts,” she says.

“I'm worried about the health of the children playing in the blood where people were shot.

“The area was not cleared even after the execution.”

Graves of those who were shot can be found all along the coast.

Ismail said his children were born in Mogadishu, a city affected by conflict for 33 years, so they are used to violence and insecurity.

But she and other parents feel playing in the blood of a convicted criminal is going too far.

However, it is difficult to stop children from joining their friends at the beach, as most parents are trying to make a living and are not always able to intervene.

Executions usually take place early in the morning, between 06:00 and 07:00.

Only journalists are invited to witness the killing, but no one stops local residents, including children, from gathering to watch.

In fact, this beach was chosen as the execution site in 1975, when Siad Barre was president, precisely because it could be monitored by nearby locals.

His military government erected a pole for some Muslim clerics who were shot dead on the spot for opposing a new family law that gave equal inheritance rights to girls and boys.

Now only the pillars remain, but crowds are not actively encouraged.

Nevertheless, parents worry that children playing at the execution site are at risk of being shot when someone is put to death.

They say their descendants are afraid of police and soldiers because they only associate them with killing people in front of them.

“I have trouble sleeping at night and feel very anxious all the time,” admits Faduma Abdullahi Qasim, who also lives within meters of the execution site.

“Sometimes in the morning you hear gunshots and you know someone has been put to death,” she says.

“I try to keep the kids inside the house all the time. We're sad and inactive. I hate going outside and seeing blood seeping into the sand next to me. .”

Although most of the nearby residents are traumatized by living near the execution site, many Somalis support the death penalty, especially members of al-Shabaab.

It is unusual for Kasim to oppose this. Especially considering that her 17-year-old son, who worked as a cleaner at a snack bar, was killed in a massive double car bombing in Mogadishu in October 2022 that left over 120 people dead and 300 dead. More than one person died. Al-Shabaab was blamed for the injuries sustained in the attack.

“I don't personally know the people who are being executed, but I think this practice is inhumane,” she says.

Children from the seaside neighborhood aren't the only ones playing on the sand near the execution site.

Young people from other parts of the city gather here, especially on Fridays, the Somali weekend.

One of them is 16-year-old Abdirahman Adam.

“My brother and I come here every Friday to swim at the beach and play soccer,” he says.

“My sister also comes dressed in her best clothes so when we take pictures she can post them and look beautiful.”

He and the others who flock to the beach know about the executions and graves of those shot there, but they go nonetheless.

For them, a beautiful central location is more important.

“Our classmates see the photos and are jealous. They don't know that we are hanging out at the execution site.”

Naima Saeed Salah is a journalist at Bilan Media, Somalia's only female media company.