A version of this article was first published in April 2020

Eddie Gray collected the ball inside the center circle and immediately aimed for Chelsea's goal. But David Webb has other ideas. Buoyed by fresh memories of being hit at the hands of the Leeds winger a few weeks earlier, the defender took both of his feet off the ground and hit him with no prisoners. Bang.

The rematch of the 1970 FA Cup final takes two minutes to live up to its billing as a game best avoided for the faint of heart.

The match was the epitome of football as an encounter of pure malice between a defeated Leeds United, known for having muscle to match their greatness, and a victorious Chelsea team, equal parts flashiness and ferocity. It has been passed down in legend.

Half a century ago, football was a very different game, with a far more forgiving attitude towards crunchy, bloody tackles and their aftermath. But even by the standards of the time, it was brutal viewing.

Its reputation has endured, and it has since been reexamined twice by key authorities according to modern interpretations of the rules. In 1997, David Herreray concluded he would show six red cards, but in 2020 Michael Oliver opted for 11 red cards.

Referee Eric Jennings waved just one yellow card that night.

As the two clubs prepare to face off in the FA Cup for the first time since that game 54 years ago, BBC Sport takes a look back at one of the most infamous fixtures in English football history.

“A special kind of hostility”

“previous”. This is a polite phrase used by many of the participants in the 1970 final to describe the history and persistent dissatisfaction that Old Trafford brought with them.

On a larger scale, Leeds vs. Chelsea epitomized the north-south divide. The Blues were seen as fashionable Southern Fancy Dans who hung out on the King's Road drinking champagne with celebrities, while the Whites smoked in working men's clubs and played in carpet bowls. He was perceived as a brooding, grumpy Northerner.

In truth, the two men were more similar than they would like to admit, both possessing raw strength and brilliance, each ambitious and on the rise. Perhaps this explains some of their bitter rivalry.

In an interview with Chelsea's website in 2018, Bonetti said: “Leeds had a name and a reputation for being dirty, so there was a rivalry. Dirty is not a very good word, so I would call them physical. “We call them physical.” “Physically we were on par with them, because we had players who were physically good and that's probably why we were a big rival. The way we played was not similar.”

Leeds midfielder Johnny Giles testified in his autobiography that there was a “special kind of animosity” between the teams.

“I had a ‘before’ experience with Eddie McCready,” Giles added. “John Hollins, who usually marks me, could do a little bit. And Ron 'Chopper' Harris made a name for himself.”

Chelsea striker Ian Hutchinson put it more simply: “We hated them and they hated us.”

Leeds still carried the scars of their 1967 FA Cup semi-final defeat to the Blues, in which they felt Peter Lorimer's superb free-kick had been missed.

In the 1969-70 season alone, the two sides met six times, with Leeds winning both league games, including a 5-2 win at Stamford Bridge, and a draw in the third round of the League Cup, with the Blues coming out on top with two games to spare. Ta.

There were also individual scores to settle, and one of the most recent was between Webb and Gray. In the drawn final at Wembley, Leeds' Scottish winger gave Chelsea's full-back an absolute boost, sparking a rematch.

Los Blancos almost had the upper hand, but somehow failed to win on the surface of the National Stadium, which was buried in a pile of sand, trying to make the match possible after bad weather.

Webb moved away from Gray in the replay, switching to centre-back to give Harris the task of silencing the winger, but fate pulled the pair back almost immediately, giving the Chelsea man a chance to make his mark.

He did this about halfway down Gray's left shin.

According to Oliver, by 2020 standards, this would give Webb his first yellow. The second goal came 12 minutes later, this time with a two-footed lunge on Alan Clarke deep in his own half, which led to the third goal in extra time. But in 1970, Jennings took the whistle out of his mouth and kept his cards firmly in his pocket.

There were further obvious violations that went unpunished. Billy Bremner was sent down the field spinning by Peter Houseman, Hunter and McCready went to bat, leaving Clark with a leg.

As noted Observer journalist Hugh McIlvanney later wrote: “At times it appeared that Mr. Jennings would only award free kicks if a death certificate was produced.”

Webb later recalled to the Daily Mail: “Every time he tried to look in his pocket to book someone, he would pull out a handkerchief, blow his nose, and say, 'Is that OK?'”

Harris had more or less finished his work on Gray before the end of the first half, grabbing the back of the winger's left knee and depriving him of arguably the most points from Leeds with an injury that ruled him out for the rest of the game. A talented offensive player.

Always a hatchet man, Harris tried to do the same to Gray's left-wing colleague Terry Cooper in the second half, but all he succeeded in doing was punching through his shorts.

Years later, as Gray was enjoying a black-tie dinner, Harris tapped him on the shoulder, held out his hand, and, laughing, asked, “What do you think?” “Can I have my studs back?”

“Bites Yer Legs” and “The Cat”

If Harris' reputation outshines him, so too does Norman Hunter, a key figure in the Leeds defence.

It would be another two years before the infamous banner reading 'Norman Bites Year Legs' was raised by Leeds fans at the 1972 FA Cup Final, but his uncompromising style was Widely known.

His first touch, a throw-in, in the 1970 rematch was loudly booed by Chelsea fans. His second meaningful involvement would provoke a more violent reaction.

After giving up the ball after moving forward, Hunter and McCready link up in midfield, leading to a short flurry of strikes after challenges.

Late in the match, the Leeds defender is seen prowling after another heavy challenge, his fists clenched and ready for battle.

For many, it's an unforgettable image of Hunter on the pitch, but for a player whose silk rivals steel, it's a huge blow. He won 28 caps for England and was part of the 1966 World Cup winning team at the age of 22.

It was in no way representative of this man. He was a warm, generous and much-loved man and his death on April 17, 2020 has left Leeds and the whole of football deeply saddened.

“I worked with him on the after-dinner circuit,” Harris told the Mail. “On the field he was an animal, but outside of football you'll never meet a nicer guy, a gentleman.”

Just five days before Hunter's death, Chelsea lost one of their all-time heroes in Bonetti. His influence over the 240 minutes of the 1970 final was perhaps greater than any other player.

His bravery in scoring in the first leg at Wembley was one of the main reasons for the rematch, but even this fine performance was overshadowed by the fortitude he showed at Old Trafford. has become thinner.

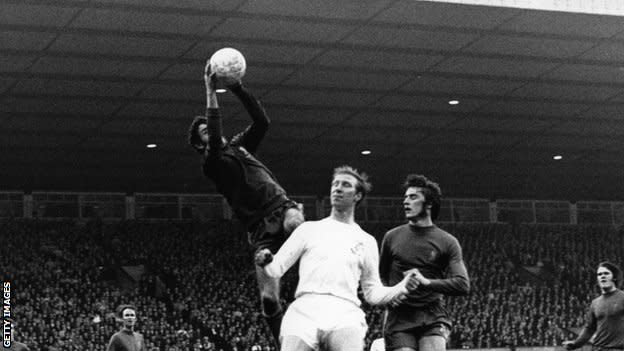

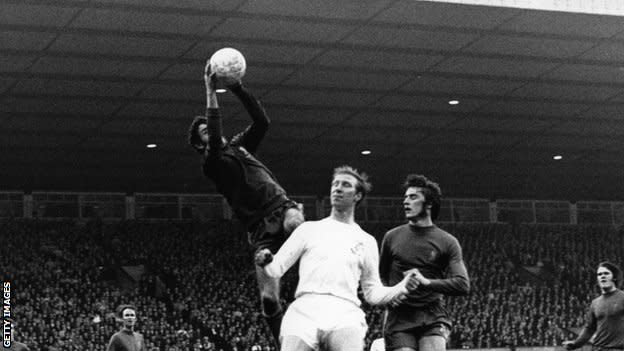

In the 31st minute, he suffered a knee injury in a fierce aerial duel with Leeds forward Mick Jones, which required long-term treatment, with BBC commentator Kenneth Wolstenholme saying: “This almost deserves an X rating.” did. He appeared after half-time, heavily tied up and unable to take a goal kick.

Jones capitalized on that immediately after his injury to give Leeds the lead, but Bonetti had the last laugh, living up to his 'Cat' reputation and making a series of important saves, using his one leg to his advantage.

Fittingly, Bonetti – a revered figure in Chelsea's history who laid the foundations for Chelsea's first cup final victory – retrieved the trophy's pedestal at the trophy presentation ceremony.

Karate Kick and Big Jack's Little Black Book

As the match progressed and the sky darkened over Old Trafford, the violence on the pitch only increased.

Peter Osgood fouled Jack Charlton, but Charlton quickly got to his feet and forced the striker into the turf. It was an immediate act of retaliation that the Leeds centre-back usually reserved for his infamous little black book of future victims.

This was another attempt at revenge by Charlton, who left Osgood unmarked as the defender went looking for the Chelsea player who had hit him in the thigh, scoring and giving Leeds the lead.

But the cruelest moment came in the 85th minute.

Billy Bremner, a brilliant midfield centerpiece for Leeds, always gave his all, but in 1970 he became an obvious target for Chelsea players.

Hutchinson earned the only booking of the match for shoving the Scottish player, and a fierce battle began between the two for the rest of the match, with late tackles, retaliatory kicks and each expressive A hand gesture was seen.

But it will be McCready who will deal the biggest blow. He leapt high into the box, missed a ricocheting ball, and delivered a karate kick to the head that, according to Blues defender John Dempsey, “almost cut Bremner in half.” Jennings waved play on in his final game as a professional umpire.

Hutchinson and Webb would have the decisive say and Chelsea would ultimately emerge victorious in extra time. The former's magnificent long throw hit Charlton on the head and at the back post, and the latter nodded home.

“When I saw the Leeds players I thought we could celebrate,” Webb told the Mail. “Leeds would complain about anything. If they had had a reason to claim a foul, they would have fouled and they wouldn't have complained and would have deflated.”

It was Chelsea's historic first win in the FA Cup and set them up for another silver medal in the European Cup Winners' Cup the following season.

For Leeds, it was a painful near miss in a season full of them, coming in a month that saw them relinquish a second successive league title and end their European Cup challenge at the hands of Celtic in the semi-finals.

The wounds have healed and the anger has subsided, but the infamous legacy of the 1970 final remains.

The average number of viewers watching the match at home was 28.49 million, making it the sixth largest single event in British television history and the largest for any domestic club match since then.

Leeds' 17-year-old midfielder-turned-right-back is sure to be mentioned in a special position on Wednesday. Thankfully, Archie Gray is unlikely to suffer from the treatment his great-uncle Eddie received 54 years ago.

Much has been said and can still be read about that wild replay at Old Trafford. But perhaps the most obvious memory is of Leeds' right-back Paul Madeley that day: “It was just the way the game was played back then''.